Aviation doesn’t ban aircraft lightly. Grounding a type means airlines lose millions, schedules unravel, and public confidence takes a hit. Regulators know the weight of that decision. So when a modern airliner is pulled from the sky worldwide, something serious has gone wrong.

That’s exactly what happened with the Boeing 737 MAX.

Not a prototype. Not an experimental design. This was supposed to be the most advanced version of the world’s most popular jetliner. Instead, it became the center of the most uncomfortable chapter in modern commercial aviation.

A familiar airframe pushed a little too far

The 737 lineage stretches back to the late 1960s. Airlines love it because it’s predictable, economical, and fits into existing infrastructure. Pilots can transition between variants without retraining from scratch. That continuity is worth a fortune.

When Airbus launched the A320neo with more fuel-efficient engines, Boeing faced pressure to respond quickly. Their answer was the 737 MAX — upgraded engines, improved range, better economics. On paper, it made perfect sense.

The trouble came from those new engines.

They were larger than anything the 737 had originally been designed to accommodate. To make them fit under the wing, Boeing moved them forward and higher. That altered the aircraft’s aerodynamics in subtle but critical ways, especially during high angle-of-attack situations.

Instead of redesigning the airframe, Boeing chose a software solution.

MCAS: a system most pilots didn’t know existed

The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS, was intended to make the 737 MAX “feel” like earlier 737s. It automatically trimmed the nose down under certain conditions to prevent an excessive pitch-up.

In theory, it was a safety enhancement. In practice, it relied on input from a single angle-of-attack sensor. If that sensor fed bad data, MCAS could activate repeatedly, pushing the nose down again and again.

That’s not a hypothetical. It happened.

Lion Air Flight 610 crashed in October 2018. Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 followed in March 2019. Two aircraft. Two crews fighting a system they were barely briefed on. 346 lives lost.

Within days of the second crash, regulators across the world grounded the 737 MAX. Airspace that normally stays open to everything from ancient freighters to experimental test flights suddenly closed its doors to one specific aircraft type.

That’s what “banned from flying” looks like in the real world.

Why this grounding felt different

Aircraft get grounded for technical issues all the time. Cracks discovered. Engines pulled for inspection. Fleets temporarily parked. This was different. The grounding lasted nearly two years in some regions. Deliveries stopped. Airlines parked brand-new jets in desert storage.

Trust had fractured.

Pilots felt excluded from the system’s logic. Regulators felt they hadn’t been given the full picture. Passengers began checking seat maps and aircraft types before booking flights, something only the most aviation-aware travelers used to do.

The problem wasn’t that technology failed. Aviation deals with failures every day. The deeper issue was how the system had been designed, communicated, and certified.

What brought the aircraft back

The 737 MAX didn’t return to service because the world “moved on.” It returned because the aircraft changed.

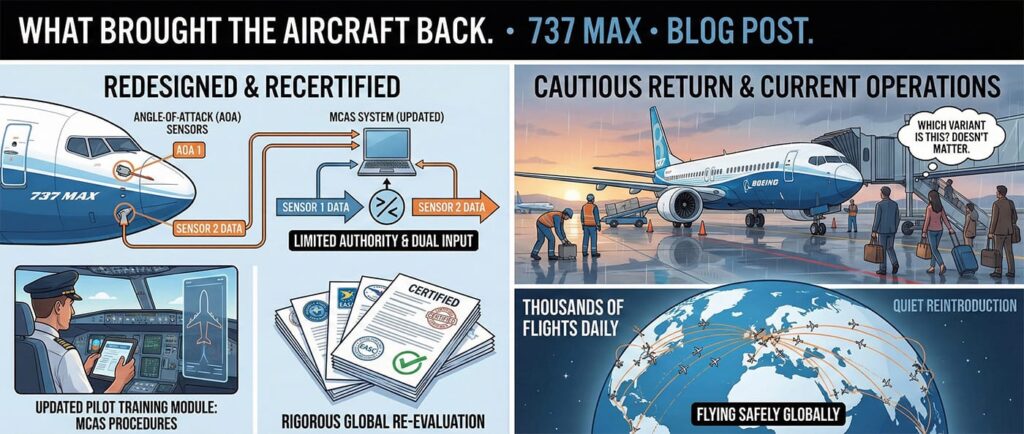

MCAS was redesigned to use data from both sensors. Its authority was limited. Pilots received updated training. Certification processes became more rigorous. Every major regulator conducted its own independent evaluation rather than relying solely on the FAA.

Even then, the return was cautious. Airlines reintroduced the aircraft quietly. No fanfare. Just slow, careful integration back into daily operations.

Today, the 737 MAX flies safely around the world. Thousands of flights every day. Most passengers never know which variant they’re on.

Still, the story hasn’t faded.

Why this matters beyond one aircraft

The 737 MAX grounding reshaped conversations across the industry. About automation. About human factors. About corporate culture. About regulatory independence. Engineers, pilots, and safety professionals still reference it when debating how far software should be allowed to compensate for airframe limitations.

It also changed how enthusiasts and collectors view modern aircraft. When you study a detailed replica of a 737 MAX cockpit, you start noticing things that photos rarely make you think about — the reliance on screens, the layered logic of flight control systems, the way modern jets quietly manage risk in the background.

A museum-quality model doesn’t tell the story by itself. It invites you to ask better questions.

That’s what this aircraft ultimately represents. Not just a ban. Not just a tragedy. A moment when aviation had to pause, look at itself honestly, and decide how it wanted to move forward.

Those moments are rare. They’re uncomfortable. They’re necessary.

And they leave behind lessons that shape everything that comes next.